Originally published in Antenna from the University of Wisconsin – Madison, 10 August 2012.

Thank you, thank you very much,

I can’t express it any other way.

For with this awful trembling in my heart,

I just can’t find another thing to say.

I’m happy that you liked the show,

I’m grateful you liked me.

And I’m sure to you the tribute seemed quite right.

But if you knew of all the years,

Of hopes and dreams and tears

You’d know it didn’t happen overnight.

Huh, overnight!

I imagine these words whispered back to all the moving tributes from family, friends, and fans of Alex Doty, an influential scholar whose generosity exceeded any metrics of greatness and whose untimely passing will be mourned by many generations of scholars to come. These words I use because they preface a lyric with which Alex introduced himself: “I was born in a trunk at the Princess Theater in Pocatello, Idaho.” But I also use them here because they were first uttered by one of Alex’s own early inspirations, Judy Garland, in the same number in the same film, A Star is Born (1954), which also happens to be the year in which Alex was born.

into participating in my Console-ing Passions panel in July 2012.

I did not know him personally as many of you did, nor do I share the library of memories you may have of him. But I wanted to write a piece about how his life and his work has inspired my own as a young academic to demonstrate the ways in which, like such diva figures as Judy Garland, he will continue to inform and empower young queer individuals such as myself long after his or my time.

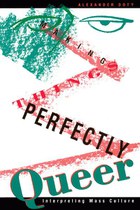

The first article I ever presented in a graduate seminar and one of the first queer theory pieces I ever read, was the first chapter of his book Making Things Perfectly Queer entitled “There’s Something Queer Here.” I found myself fervently and excitedly highlighting passages as though they’d been written especially for me and jotting them down on a legal pad so as not to lose them in the sea of other articles I was struggling to read week after week.

The first article I ever presented in a graduate seminar and one of the first queer theory pieces I ever read, was the first chapter of his book Making Things Perfectly Queer entitled “There’s Something Queer Here.” I found myself fervently and excitedly highlighting passages as though they’d been written especially for me and jotting them down on a legal pad so as not to lose them in the sea of other articles I was struggling to read week after week.

I come back to it often and reference enough of his other work that Alex seems to hold a consistent spot in my bibliographies. Indeed this chapter made me recall one of the first moments in which a media text informed my own struggle with sexuality and the feelings of difference I was beginning to experience as a young child raised in a rural, homophobic environment, which I wrote about later that fall:

“I can, with great clarity, remember the precise moment when everything fell into place: I sit motionless on the couch, staring at the TV, images flickering before my glazed but pensive adolescent eyes. Bewitched is on, and I’m left alone in the dark basement, sheltered and away from the homophobia and hate shouted at me all day in school. I’m in a sort of meditative state—receptive to what I’m watching, laughing on cue, performing my role as the audience but understanding only the face value. Something snaps, and I think, ‘Why should she have to hide a part of herself to fit in?’ And then there comes this single, beautiful, intimate moment. My eyes water, my nostrils flare, and I breathe out a sigh as I begin to smile. Samantha is me.”

I did not have the language at that young age to describe my experience of Bewitched as a queer reading nor did I give any other interpretation of it much more than a passing thought. I might not have understood what sexual identity meant or in what ways I was different, but something about dissolving myself into Samantha’s colorful world with her unwed, flamboyant, and powerful mother along with a parade of queer magical beings made me covet life outside her broom closet. These sorts of reading strategies–of finding or making a space for queerness on television (perhaps not strategies at all)–are not, as Alex writes, “‘alternative’ readings, wishful or willful misreadings, or ‘reading too much into things’ readings. They result from the recognition and articulation of the complex range of queerness that has been in popular culture texts and their audiences all along.”

I did not have the language at that young age to describe my experience of Bewitched as a queer reading nor did I give any other interpretation of it much more than a passing thought. I might not have understood what sexual identity meant or in what ways I was different, but something about dissolving myself into Samantha’s colorful world with her unwed, flamboyant, and powerful mother along with a parade of queer magical beings made me covet life outside her broom closet. These sorts of reading strategies–of finding or making a space for queerness on television (perhaps not strategies at all)–are not, as Alex writes, “‘alternative’ readings, wishful or willful misreadings, or ‘reading too much into things’ readings. They result from the recognition and articulation of the complex range of queerness that has been in popular culture texts and their audiences all along.”

Building on Alex’s influence, I am launched into scholarship invested in finding other rural queer individuals and relaying their stories of using the media for identity work. Drawing from a pool of other reception scholars, Alex encourages the use of ethnographic work to re-imagine the audience not within pre-established categories but rather to investigate their daily life and how they integrate media into it. Putting the “I” back in our work in feminist tradition and being reflexive of our own media practices and subjectivities, as Matt Hills argues, is useful in conveying “the tastes, values, attachments, and investments” of the communities from which we write that our own voices can help illuminate. These are the stakes involved in our research, and as Alex himself writes defending his use of the word queer, “I want to recapture and reassert a militant sense of difference [and] suggest that within cultural production and reception, queer erotics are already part of culture’s erotic center.”

My future in research will be difficult as it cannot rely on essentializing or over-theorized assumptions about audiences and does not have many precedents from which to be informed. I am often subject to a feeling of “imposter syndrome” and constantly worry that I will be “found out” as a fraud. In our email exchanges, however, Alex’s magnanimous generosity with me by showing interest in my work has and will continue to make me feel as though I’m on the right track. Found in the lyrics that open this post, which I imagine to be true of Alex’s life, success comes from years of hopes and dreams and tears, “it didn’t happen overnight,” and as I move forward, I like to think I’ll remember and be encouraged by the words that close his song: “This is it kid, sing!”