A small Kansas carnival, 1905: From the four corners of the earth, acts to delight, to thrill, and to mystify. There’s a fire breather, a strong man, a stilt walker. A mammoth hot-air balloon looms in the distance and beyond that clouds promise a wicked storm. A magician cowers in his wagon after a young paralyzed girl begs him to walk again. She naively believed in his powers, as did her parents and all the good, simple-minded Kansans in attendance.

A knock on the door reveals the magician’s sometimes-love, Annie, who has come to tell him of her engagement–to see if he wants her back.

“You could do a lot worse than John Gale, he’s a good man,” Oz explains. “I’m not. I’m many things, but a good man is not one of them. See, Kansas is full of good men: church-going men that get married and raise families. Men like John Gale; men like my father, who spent his whole life tilling the dirt, just to die face down in it. I don’t want that Annie; I don’t want to be a good man. I want to be a great one.”

So begins the story of Disney’s Oz the Great and Powerful, but its tale isn’t new. Everyone is trying to get out of Kansas, to get the heck out of Dodge [City, Kansas]; to get over the rainbow. And it’s no wonder, really, given what the pictures show.

Hollywood is baffled by Kansas and represents it as a simultaneously old-timey homeland as well as a sideshow of rural curiosities. Audiences watch their screens with wonder as Kansans willingly endure the plight of their harsh geography. These voyeurs know their visit to the prairie will be brief, and they’ll delight in retelling its banal but bewildering splendor: men tilling dirt just to die face down in it.

Kansas has become a carnival unto itself.

All black and white photography is abstract. Likewise, when Kansas is represented, monochromatic or not, it’s always an abstraction from an urban reality, and one saddled with disaster:

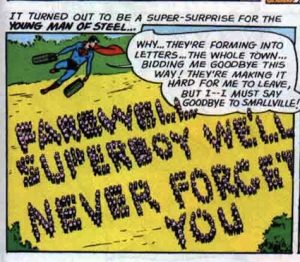

It could be something like a tornado (The Wizard of Oz, Oz the Great and Powerful, Greensburg), or a meteor shower (Superman, Man of Steel [upcoming]) that destroys your town and leaves you battling an unending parade of hybrid alien “supers”(Smallville). Maybe you’re attacked by nomadic American vampires (Near Dark), renegade Indians (Custer, Four Feather Falls), or just good old-fashioned aliens (Mars Attacks!).

If you’re lucky, you might only have to face down the occasional bandit (Gunsmoke, Winchester ’73, Dodge City, The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, etc.), or mobster (Prime Cut, The Ice Harvest), or time traveler (Looper), or errant supernatural being (The Ghost and Mr. Chicken, Courage the Cowardly Dog).

If you’re not so lucky, you’ll be confronted with domestic homicide (In Cold Blood, Murder Ordained) the American Civil War (Dark Command, Touched by Fire: Bleeding Kansas), the Great Depression (Paper Moon), racial segregation (The Learning Tree; Good Luck, Miss Wyckoff), nuclear catastrophe (The Day After), or the subsequent post-apocalyptic world (Jericho).

But more often than not, yours will be a crisis of identity. Dorothy, Superman, Oz: As queer figures unable to assimilate, they struggled through the exceedingly mechanical, zombie-esque homogeneity of Hollywood’s Great Plains, where idle-minded Kansans are born and die without living–a spectacle so unspectacular, it’s a kind of curious queer rurality. But Hollywood’s representations of Kansas go far beyond the mere trope of the rural vs. the urban. Kansas is at once more sinister as it is more sympathetic.

In the pictures, Kansas’ story is one of Bildungsroman, where a character completes a coming-of-age moment, a transition from naiveté to maturity that often involves leaving the state in one capacity or another.

In the pictures, Kansas’ story is one of Bildungsroman, where a character completes a coming-of-age moment, a transition from naiveté to maturity that often involves leaving the state in one capacity or another.

It is only in so doing that they too will learn of Kansas’ banal allure. Superman doesn’t become the Man of Steel until he leaves his small farming community to help those who really need him in Metropolis. Oz doesn’t understand the power of goodness and the 2.35:1 widescreen aspect ratio until he crash lands in his future kingdom. And, sure, Dorothy heads back to Kansas, but does so knowing that on the other side of the rainbow is a splendid world of technicolor with yellow brick roads, giant lollipops, and a wicked witch who skywrites.

Dorothy’s unyielding pursuit to return to banality only proves Hollywood’s rule: Something’s the matter with Kansas. Its bearded ladies and conjoined twins, its dog boys and elephant men, all dressed over to appear as paeans to normativity. But their queer particularity shows at the seams, and queerer still is that they’re all willing participants in their own spectacularization. They all want to be in Kansas where they could be meteored, bombed, abducted, or tornadoed at any moment, and “isn’t that queer?!”

As a gay Kansan (and I’m talkin’ tumbleweed Kansas) with a weakness for Judy Garland, few people can identify with Dorothy’s journey more than me. Given the nature of the film, I should think it would surprise some of you to hear that The Wizard of Oz is a highly cherished icon-cum-commodity for the Sunflower State. We have regarded it as a great love story to Kansas. But it’s not really, is it?

It isn’t Oz, the munchkins, the witches, or even the eccentric Emerald City dwellers that are queer to the “mass audience” of the film. Not really. The world they know is in color; it’s filled with good and evil, and often draws those lines based on appearance. The world of wonder, then–the queerness of The Wizard of Oz–was always in the telling of Kansas–it was always on this side of the rainbow. There really is no place like home!